A Building Sanitary System is the complete plumbing and drainage infrastructure within a building—covering everything from supplying clean water to collecting, treating, and discharging wastewater generated by occupants. It’s the invisible backbone of everyday comfort. While users rarely see these systems, the absence of a well-designed one directly affects hygiene and overall quality of life. In short, a properly designed and installed sanitary system ensures a continuous supply of clean water and the safe removal of waste and used water, reducing risks to health and the environment and enhancing day-to-day comfort. It is therefore a critical pillar of building engineering that demands careful design and construction.

Core Functions of a Building Sanitary System

Potable (Clean) Water Supply : The system delivers clean, potable water to fixtures throughout a building—taps, basins, showers, and sanitary ware—so occupants have adequate water for daily use. It must maintain appropriate pressure and flow across all floors to ensure efficient, comfortable usage.

Wastewater Management : The system collects and conveys used water out of the building. Wastewater is typically divided into two main types: blackwater (from toilets and urinals) and greywater (from washing, bathing, and other uses). Both are routed to treatment systems before discharge. Separating blackwater from greywater reduces treatment load and helps prevent blockages. A robust wastewater system also includes vent piping to prevent negative pressure in drain lines, which can cause odor backflow and poor drainage.

Stormwater Management : The system captures and drains rainwater from roofs, terraces, and building perimeters to prevent ponding and flooding. Downpipes and roof drains convey rainwater to suitable discharge points—such as combined building drains or public storm sewers. Good stormwater design considers slopes, adequate pipe sizing, and debris screens to prevent blockages. Otherwise, leaks, seepage, and mold from trapped moisture can occur.

Together, these three subsystems ensure a safe, sufficient supply of clean water while efficiently removing wastewater and stormwater—protecting occupants and the building structure.

Key Components of a Building Sanitary System

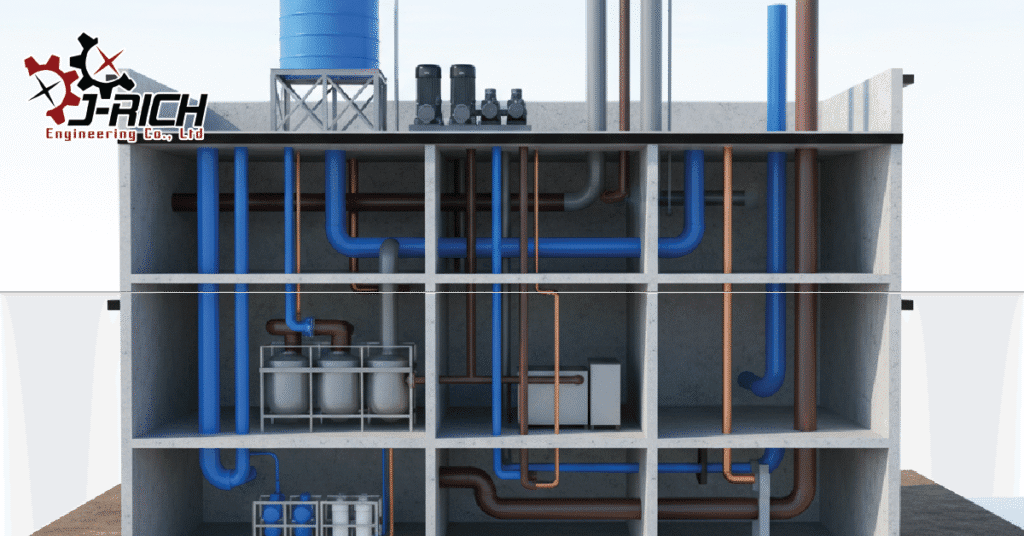

(Illustrative example: coordinated piping and sanitary fixtures working together to deliver clean water and remove wastewater efficiently.)

A sanitary system consists of multiple elements working in concert to provide end-to-end functionality. Key components include:

- Supply and Drain Piping:

Networks that convey potable water into the building and wastewater out. Potable lines often use pressure-rated materials (e.g., galvanized steel, PVC for pressure service); wastewater and storm lines commonly use PVC or PE for corrosion resistance and clog prevention. Systems also include vent piping connected to soil and waste lines to release gases and equalize pressure, reducing odors and improving flow. - Pumps and Water Meters:

Multi-story or high-demand buildings typically require pumps to move water to rooftop tanks or directly into distribution mains at adequate pressure. Water meters measure consumption at the building inlet or per floor/unit for monitoring and billing. - Valves and Faucets:

Isolation valves (e.g., gate, ball) are placed throughout the network for maintenance and emergency shutoff—at the building main and by zones/floors. Faucets and showers are points of use; modern sensor-activated fixtures help reduce touch points and conserve water. - Sanitary Fixtures and Bathroom Equipment:

Toilets, basins, urinals, bathtubs, etc., connect to the potable system for supply and to soil/waste lines for discharge. Proper installation includes P-traps/U-traps with water seals to prevent odors from traveling back into occupied spaces. - Grease Traps:

Interceptors for kitchens and canteens that capture fats, oils, grease (FOG) and food solids before wastewater enters building drains. They prevent blockages and odors by allowing grease to separate and float while pre-filtered water exits to the waste line. - Septic Tanks and Wastewater Treatment Units:

Small buildings may use septic tanks and soakaways for onsite treatment. Larger buildings often use packaged treatment plants or centralized systems (aeration/biological processes) to meet effluent quality before discharge to public sewers. - Floor Drains and Access Points:

Floor drains on wet areas (bathrooms, balconies, roofs) collect water and route it through trapped fittings to main lines. Manholes and cleanouts are placed at intervals for inspection and rodding, making maintenance easier and more effective.

When these components are properly coordinated, the system delivers smooth, safe, and hygienic water supply and drainage. Missing or poorly designed elements can cause downstream problems.

(Illustrative note: orderly piping in service corridors—with manholes/cleanouts at intervals—simplifies maintenance and reduces clogging or leakage risks.)

Consequences of Inadequate Sanitary Systems

- Health Risks:

Ineffective systems can contaminate potable water or allow sewage leakage indoors, creating breeding grounds for pathogens and vectors. This directly threatens occupant health. Conversely, upgrading sanitation to standards yields significant public-health gains—preventing waterborne diseases (cholera, typhoid, diarrhea) and reducing exposure to hazardous microbes and chemicals. - Offensive Odors:

Poor sanitary design (e.g., missing vents, dry traps) allows sewer gases to backflow through fixtures and drains. Beyond discomfort, gases like methane or hydrogen sulfide can pose health hazards at high concentrations. - Leaks and Structural Damage:

Defects can lead to hidden leaks in walls/floors, roof ponding and seepage, or leaking treatment tanks. Moisture degrades finishes, fosters mold, corrodes reinforcement, and shortens structural life. Preventive design and approved materials (plus backflow protection) are essential. - Flooding and Water Damage:

Inadequate storm drainage causes ponding around foundations or basements during heavy rain, damaging landscaping, pavements, and structural elements. Proper external drainage to public outlets prevents on-site flooding, ground saturation, and settlement-related cracking. - Environmental Impact:

Untreated discharges pollute natural waters—causing discoloration, foul odors, ecosystem damage, and disease spread via insects and pathogens. Compliant treatment and odor control reduce community and environmental burdens.

In short, shortcomings range from minor annoyances (slow drains, odors) to major issues (structural damage, disease outbreaks). Investing in sound design and installation from the start is far more cost-effective than fixing systemic failures later.

Standards and Regulations

Because sanitation safeguards health and safety, multiple codes and standards govern design and installation:

- Thai Standards:

The Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning publishes Construction Standards (e.g., “MoPH/DPW standards”), such as Sanitary Piping Standard (e.g., 3101-51) specifying materials and selection for potable and waste lines, fixture installations, on-site treatment, and venting. Engineers and architects reference these to ensure safety, durability, and hygiene (e.g., using certified, application-appropriate pipes; avoiding improvised substitutes). - Building Control and Local Ordinances:

National building control laws require adequate sanitary provisions: sufficient toilets, reliable water supply, connection to public sewers or on-site treatment, and robust storm drainage. Local ordinances often mandate grease traps and wastewater treatment for restaurants, hotels, and commercial buildings. Non-compliance can block construction permits or occupancy approvals. - International Codes and Professional Guidance:

Globally referenced frameworks include IPC (International Plumbing Code), UPC (Uniform Plumbing Code), ASHRAE guidance related to water quality and Legionella control in hot/cold water systems, and WHO sanitation guidelines. Adopting recognized standards protects occupants and the environment and builds investor/buyer confidence.

Bottom line: both Thai and international standards aim for safe, code-compliant, hygienic systems. Project stakeholders should study and strictly apply the relevant requirements.

Emerging Technologies in Building Sanitation

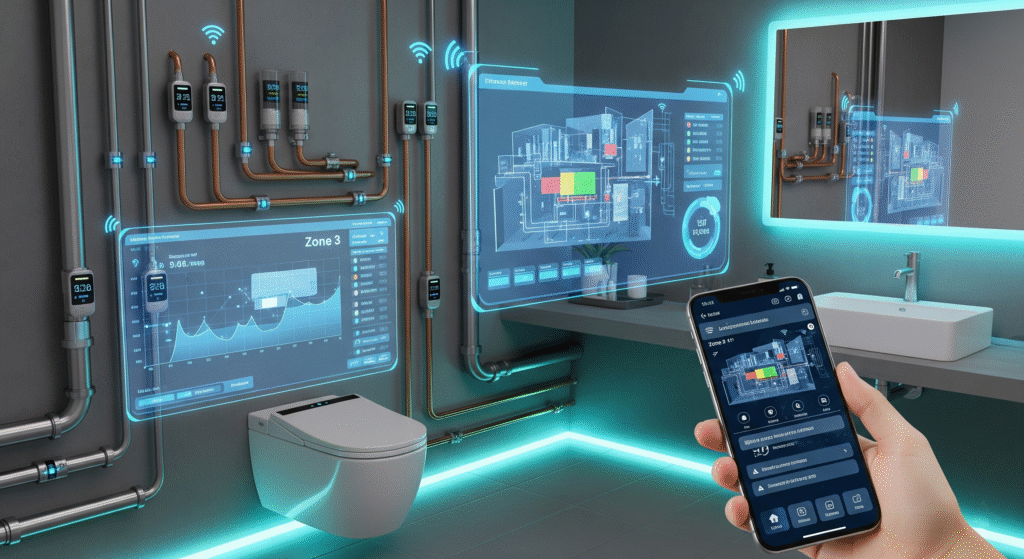

- Smart Sensors and IoT:

Real-time monitoring of flow, pressure, tank levels, and leaks; automatic alerts via BMS or mobile apps; sensor-activated fixtures to reduce water use; and smart water meters for usage analytics and leak detection—preventing small issues (like pinhole leaks) from becoming major failures while cutting O&M costs. - Water Recycling and Reuse:

Greywater recycling (from basins, showers, bathtubs, laundry) for irrigation, toilet flushing, or certain cooling needs—via automated filtration, storage, and distribution—reduces potable demand. Rainwater harvesting adds resilience and conservation with level sensors and automatic mains backup control. - Compact, Automated Treatment Systems:

Packaged biological treatment units with aeration, advanced filtration, in-tank quality sensors, and cloud-enabled controls deliver higher effluent quality with less hands-on oversight—cutting odors and extending equipment life.

Green-building strategies further promote low-flow fixtures, dual-flush toilets, aerated faucets, and environmentally friendly treatment chemicals. The future points to smarter, more efficient, and safer systems for both people and the planet.

Conclusion

Sanitary systems are foundational to occupant well-being. Though hidden behind walls and floors, their impact on quality of life and building longevity is immense. When designed to standards and properly installed, buildings enjoy uninterrupted clean water, hygienic wastewater removal, odor-free spaces, minimal leaks, and reduced environmental impact. Neglect, by contrast, risks occupant health, brand reputation, and asset value.

Whether a small residence or a high-rise commercial tower, investing in a quality sanitary system is essential. Engineers and architects should collaborate from early design stages to tailor layouts to building typology, select certified components, reserve access for maintenance, and track new technologies that improve performance. When the sanitary system runs as intended, occupants can live and work with confidence, comfort, and good hygiene throughout the building’s life.

References

- A building sanitary system manages all water flows in a building—from potable water supply to wastewater treatment and discharge—to use water efficiently and protect the environment. [ udwassadu.com ]

- Sanitary systems comprise potable water, blackwater, greywater, wastewater treatment, vent piping, stormwater drainage, and external site drainage. [ wazzadu.com ]

- Core components include various pipe types, pumps, water meters, valves/faucets, grease traps, septic tanks, floor drains/gratings, sanitary fixtures, wastewater treatment tanks, and vent systems. [ bimspaces.com ]

- Inadequate sanitation is a major global cause of disease; improving sanitation yields significant health benefits for households and communities. [ th.wikipedia.org ]

- Untreated wastewater harms aquatic life and nearby ecosystems, disrupts natural balance, degrades the environment, and threatens public health as a breeding ground for pathogens. [ pcd.go.th ]

- MoPH/DPW Standard 3101-51 (Sanitary Piping Standard, 2008) by Thailand’s Department of Public Works sets design/installation requirements for sanitary piping used nationwide. [ yotathai.com ]

- Smart plumbing technologies use sensors and IoT to monitor flow/pressure, detect leaks, and control water use in real time (e.g., sensor faucets and fixtures) to reduce wastage. [ innodez.com ]

- Greywater recycling: water from sources like basins and showers is filtered, stored, and reused (e.g., for irrigation or toilet flushing) via automated systems, reducing potable water demand. [ innodez.com ]